“Terry Gilliam’s ferociously creative black comedy is filled with wild tonal contrasts, swarming details, and unfettered visual invention — every shot carries a charge of surprise and delight.”

Nigel’s intro

Brazil is a film Wayne and I have wanted to show since we started the film club so we are very grateful to Steve, Jonathan and the rest of their quiz team for picking it from our list of also rans. (It lost the vote last year to Orson Welles’ The Trial in our ‘kafkaesque’ themed vote after Ministry of Fear).

The film is directed by Terry Gilliam and came out in 1985. Without question, it is his greatest movie.

I first saw it when I was a teenager. I bought the video. I loved Monty Python, particularly The Holy Grail, which Terry Gilliam co-directed with Terry Jones and I loved his non-Python films too - Jabberwocky, Time Bandits and even The Adventures of Baron Munchausen which I remember dragging my parents and my younger brother to see in the West End during a school holiday trip to London. I was the only person in my family who had a good time watching that.

So this is a film I’ve loved for years and have revisited many times too. I think when I first saw it what appealed was it just felt so unique in its imagery and tone. It has this Pythoneque anarchic comedy too.

Later I worked for 14 years at the BBC and regularly, after being confronted by some inane bureaucracy, I’d find myself asking a colleague, “Have you seen the film Brazil?” because quite often - and anyone who’s seen W1A will know this - it felt like a very resonant film in that workplace.

I think one of the reasons the film stands up so well is its themes will sadly never go away. As well the bureaucratisation of absolutely everything, the film is about social alienation, terrorism, body image and the hazards of an increasingly technology-driven society.

It also seems appropriate that we’re showing the film in the year when George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four is celebrating its 70th birthday. Gilliam claims that he’d never read Orwell’s novel when he was writing the script but its influence is all over the film.

A few years ago Gilliam spoke to Salman Rushdie for a magazine interview where he reflected: “Brazil came specifically from the time, from the approaching of 1984. It was looming. In fact, the original title of Brazil was 1984 ½. Fellini was one of my great gods and it was 1984, so let’s put them together. Unfortunately, that bastard Michael Radford did a version of 1984 and he called it 1984, so I was blown.”

Gilliam wrote the first draft with his Jabberwocky co-writer Charles Alverson but then asked Tom Stoppard to write a second draft, who added his dramatic flair to Gilliam’s images. In Stoppard’s words, “I don’t think Terry’s that interested in dialogue as a craft.”

Gilliam then wrote the final script with Charles McKeown, a writer and actor he’d first met while making The Life of Brian. You can see McKeown in the film as Harvey Lime, who shares a desk with our hero, Jonathan Pryce’s character Sam Lowry.

The film was produced by Arnon Milchan, who’s still an incredibly successful Hollywood producer. His two films prior to this were Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, which might explain why Robert De Niro was so keen to be in the film.

De Niro wanted the role of Sam’s friend Jack Lint, but Gilliam had promised that to his own pal Michael Palin. So Gilliam offered him the smaller role of the Tuttle, the rogue air-conditioning repairman.

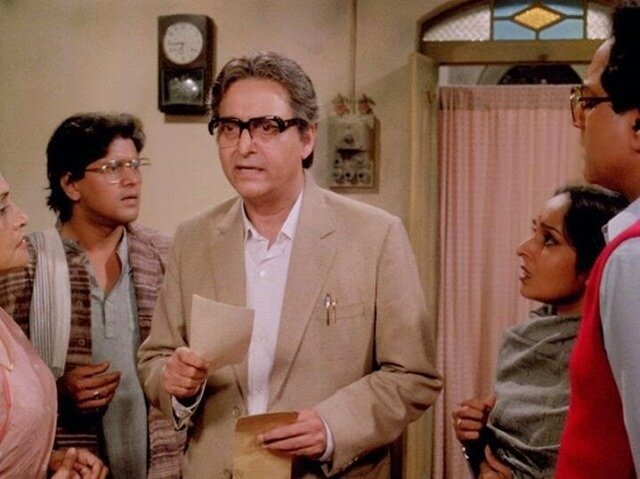

As well as Palin and Jonathan Pryce, the film is a who’s who of familiar British acting talent. Bob Hoskins, Ian Holm, Ian Richardson, Gordon Kaye from ‘Allo ‘Allo - they’re all in it.

Unusually the story about what happened to Brazil after it was made is more interesting than the making of the film. I’ll try to be brief and if you want to know more, just read Jack Matthews’ book or look up The Battle for Brazil DVD extra on YouTube.

Basically, the budget Arnon Milchan got for Brazil was $14m. $6m of that came from Fox which gave them the international rights to the film. And $9m came from Universal for the American rights.

Everywhere but the US, Gilliam’s cut was released, but Sid Sheinberg, the head of Universal found the film overlong, confusing and too downbeat and demanded a shorter cut. Contractually Gilliam was obliged to bring the film in under 2 hours 15 minutes which he didn’t - but only by a whisker. Universal cut it to a more upbeat 94 minutes. This prompted what became a vitriolic war of words, a classic David vs Goliath over art versus commerce.

Just to give a flavour this is Sheinberg talking about a memo he wrote to Gilliam:

“I told Mr. Gilliam that I had seen his last version of the film and although I felt the shortening and other editing changes constituted an improvement I nonetheless thought that the film had major problems and required substantial additional work. Mr. Gilliam told me that this was his final version of the film. That the film had been received well by various Americans… he indicated that quote ‘many people’ at Universal shared his excitement about the film. I indicated to Mr. Gilliam that notwithstanding his core commitment to his film the fact remained that a prior preview of the original film indicated a very poor reception from the audience and I felt my responsibilities precluded releasing a film that had been so poorly received by an audience without attempting to improve the film from an audience point of view. I invited his participation in such changes as we had in mind. Mr. Gilliam indicated he certainly did not want to be a party to this and that I would be the recipient of a war in quotes which would be more unpleasant than releasing the film in his version.”

And this is a memo from Gilliam to Sheinberg:

“Attention Sydney Sheinberg. Dear Syd. Once upon a time you told me that you were not the one that put me in the chair at the end of Brazil. I'm afraid that is no longer true, unable as I am to think of anyone else who is directly responsible for my current condition. Your later offer to be the friend who becomes a torturer has more than come true. I'm not sure you are aware of just how much pain you are inflicting but I don't believe responsibility to the company in any way absolves you from crimes against even this small branch of humanity.

As long as my name is on the film what is done to it is done to me. There's no way of separating these two entities. I feel every cut, especially the ones that sever the balls - and I plead whether they are done in the name of legitimate and responsible experiments or personal curiosity - if you really wish to make your version of Brazil then put your name on it. Then you can do what you like. Sid Sheinberg’s Brazil has a nice ring to it. But until that time I shall continue both to decline and also to decline. Please let me know how much longer must I endure before the bleeding stops. Deterioratingly yours, Terry.”

Gilliam mustered support by showing his film illicitly to groups of students and critics and in 1985 the film won the Los Angeles Critics Film Award for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor and Best Screenplay even though the film hadn’t been released.

Gilliam went so far as to pay $1500 to put this ad in Variety.

Eventually Universal released a slightly shorter version (under 2 hours 15 minutes) that didn’t do much business and the upbeat 94 minute version was shown regularly on American TV. For Americans, watching the version that was released here became something of a film nerd’s Holy Grail.

Over time of course, the film’s stature has only grown for all the reasons I mentioned earlier.

In these troubling times in which we live, I’m sure you’ll find the film speaks to you in one way or another.

I’m going to finish with another quote from Terry Gilliam, this time actually talking about the film, which puts a somewhat positive spin on things.

This is from an interview he did 1986 and he was asked to comment on what the interviewer calls “the rather cynical tone that infuses your comedy, from Jabberwocky through to Brazil, and even in your animated films?”

This is Gilliam’s response:

“It's amazing that you say cynical because that's come up before. I don't think I'm cynical. I'm sceptical; I don't think I'm cynical about things. The terrible fact is that I'm terribly optimistic about things. I have a theory about Brazil in that if was a very difficult film for a pessimist to watch but it was okay for an optimist to watch it. For a pessimist it just confirms their worst fears; an optimist could somehow find a grain of hope in the ending. Cynicism bothers me because cynicism is in a way an admission of defeat, whereas scepticism is fairly healthy, and also it implies that there is the possibility of change…”

BONUS INTERESTING FACT

The torture chamber is the interior of one of the giant cooling towers of Croydon Power Station. The station also provided the exterior of the Ministry, and though most, including the imposing entrance, has gone, you can still see some of the monumental deco brickwork at the foot of the two huge chimneys now on the site of the IKEA Superstore on Ampere Way.